Zebrafish may hold key to antibiotic-resistant superbug infection fight

First appeared in the Herald Sun, by Lucie Van Den Berg, 1 September 2016

TEST ALLOWS DOCS TO DISTINGUISH BETWEEN VIRAL AND BACTERIAL INFECTIONS IN SIGHT

A CHINK in the armour of a deadly superbug has been revealed, providing scientists with a potential new pathway to annihilate the antibiotic-resistant infection.

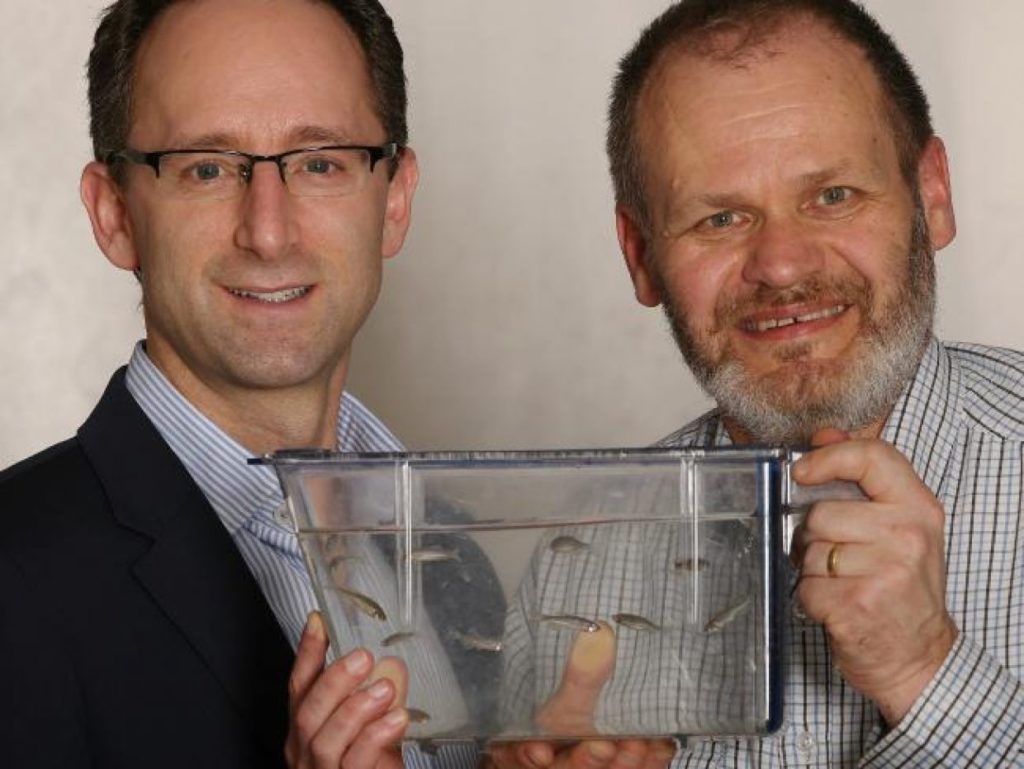

Using translucent zebrafish infected with glow-in-the-dark bacterial cells, Monash University scientists have been able to watch the war that breaks out in the body during an infection in real time.

Under the microscope, fluorescent immune cells clashed with the superbug’s glowing cells, but to the researchers’ amazement, when they adjusted the bacteria, it prompted an incredible response from the immune system.

“By blocking a metabolic pathway in the bacteria, the immune system triggered an enhanced response to the infection, which increased its defence and helped it fight off the infection more rapidly,” lead author and infectious diseases and microbiology professor Anton Peleg said.

As antibiotic use increases in humans and animals, the rise of bacteria that is resistant to available drugs has also risen, posing a serious public health concern.

This particular superbug, acinetobacter baumannii, is one of the world’s most problematic, causing life-threatening illnesses, predominately in hospital patients.

The researchers from the Monash Biomedicine Discovery Institute, Department of Infectious Diseases and Australian Regenerative Medicine Institute initially set out to find out if zebrafish could be a good model for studying the disease the superbug causes.

Believe it or not, the zebrafish has a very similar immune system to humans.

Prof Peleg said researchers ended up identifying a potential way to destroy the superbug. When they made a mutant of the bacteria, by blocking a key metabolic pathway, they discovered it led to a build-up of a molecule, which was like a red flag for the immune cells because they suddenly rushed in to clear it out.

“Not only did we achieve improved bacterial clearance, we reduced the severity of the disease,” Prof Peleg said.

“If we could find an antibiotic that targets that pathway and inhibits it, it could be an entirely new way of fighting off superbugs, which is desperately needed because we are running out of antibiotics.”

The researchers believe this new pathway may also play a key role in other types of superbugs. The work is published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Read the article here.