Sharks could reveal how neck disease forms in humans

As published in the Health Canal October 19 2015

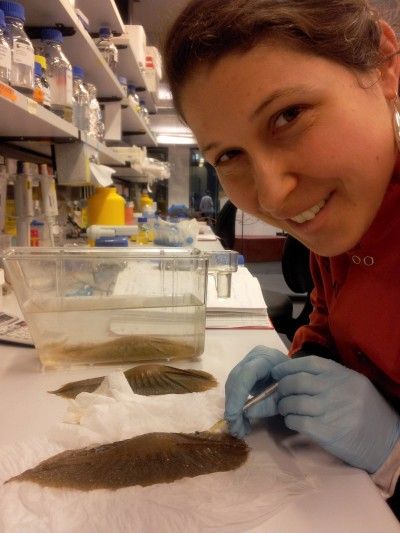

Researcher Catherine Boisvert conducts egg drug injection work for the project.

New insights into how the neck vertebrae of elephant sharks naturally become fused could help researchers to understand how neck development can go wrong in people affected by disease.

In a paper published in journal, PLoS One, researchers from Monash University’s Australian Regenerative Medicine Institute (ARMI), Curtin University, the Natural History Museum, London and the Australian Synchrotron, investigated how the fused neck developed in elephant sharks.

In people with the disease known as Klippel-Feil syndrome, the vertebrae of the neck becomes fused, but in living sharks and rays, and in some fossil armoured fish called placoderms, having a neck encased in bone is normal.

Lead researcher, Dr Catherine Boisvert, ARMI, said knowing how this fused neck formed under normal conditions could be the first step in understanding how neck development can go wrong in people when affected by disease.

“In some animal species, part of the animal’s body mimics what we see in a human disease. These species are known as ‘evolutionary mutants’, and analysing them provides unprecedented access to information in a healthy individual.”

“We are gaining a better understanding on how these morphologies develop and what developmental pathways (genes and their networks) are involved in producing them. This knowledge may help us better understand the disease in humans.

The researchers grew elephant sharks collected from eggs laid in captivity on the Mornington Peninsula, Victoria. They stained them to study the fused neck, called the synarcual, and reveal cartilage and muscle development. They also analysed the fossils of placoderms, providing a high level of data on how this fusion occurred for comparison to living animals.

Using microscopic imaging at the Australian Synchrotron, the researchers found that neck vertebrae in the elephant shark and placoderm developed normally, and only later became fused after emerging from their egg. Skates and rays appeared to show a similar pattern, suggesting this may be a normal condition for vertebrate animals in general.

This contrasts the belief that a fused neck forms because individual vertebrae fail to form in early development.

Dr Boisvert said the next step is to look further into the genes that are responsible for this fusion in the shark species and apply them to diseases of the human spine.

The way the synarcual develops in placoderms and sharks is most similar to human disease Fibrodysplasia Ossificans Progressiva, which slowly turns soft tissues to bone – patients are born with a normal skeleton, with fusion occurring subsequently.

“Sharks don’t have true bone – instead they have a hard kind of cartilage called prismatic calcified cartilage – and we don’t fully understand yet if the vertebra fusion is due to overdevelopment of cartilage, or if the soft tissue between the vertebrae becomes transformed into cartilage, resulting in fusion,” Dr Boisvert said.

“These sorts of ‘metaplastic’ transformations of the spine have been observed in farmed salmon, and exciting new research is beginning to unravel the genes involved in these transformations. Our goal is to do the same for elephant sharks, rays and skates.”

“All in all, we are coming closer to understanding how a fused neck develops normally or under stressful conditions (as is the case for farmed salmon) in a range of vertebrates at the base of our ancestry.”